It was an odd time and place to have my eyes well up with tears, but what I was watching had been suddenly, inexplicably, transformed into a meaningful and encouraging exhortation offering solace directly to – or from- a deep and wounded place within me. But because I was surrounded by a whir and whishing of industrious friends and family in our garden, I quickly wiped the tears from my cheeks without taking time to sit with that message or with the emotions it stirred up within me. Three weeks have passed since that day, and while my landscaping project impatiently waits for the rain to stop and the next phase to proceed, I want to do a little digging into that free and unexpected moment of therapy.

The Neighbor

That morning I woke up to the penetrating sound of a jack hammer outside of my window. Our neighbor, Bela, was already sitting in the open cabin of the excavator we had rented and, with the jack attachment, was skillfully demolishing a low concrete wall which has vexed me for the last twenty four years. Over the years, Bela (Bay-la), the very German man with a deep, loud, and gravely voice that lives across the street from us, has become an unlikely friend of my husband’s and a Godsend to both of us.

My husband and I both studied Theology, Religious Instruction to be more exact, so it would be fair to say we fall into the academic side of things, actually, perhaps even the most abstract side of the academic side of things. Theology is basically a swirl of philosophy, sociology, and psychology, but beyond studying the ideas behind the actual things and behavior, we studied the often intangible realities behind the ideas behind the things and behaviors. In addition, my husband is a musician. That means in our home there is a lot of singing, whistling, guitar playing and talking about why things are the way they are and how they might be instead. The flip side of that is that neither of us has become a master of the things themselves. So when it comes to realizing my dreams for our home and garden, we plod along slowly with the enthusiasm of DIYers who would rather be, and be better at, reading and writing poetry than pouring or breaking up concrete.

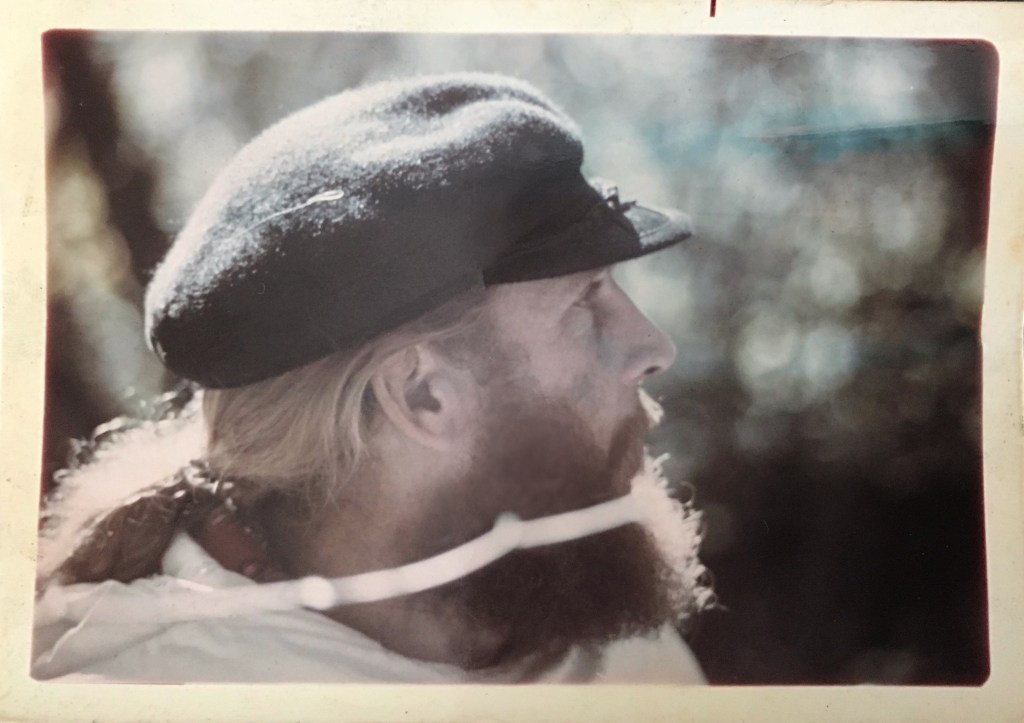

Not so with Bela. He is much better adept to this world of things than my husband or I are, and he has become a valuable point man, mentor, and resource at innumerable junctions during our ongoing renovations. Not long before, he had retired from his many years as a construction worker and is still licensed to operate just about every construction machine there is. He was not only a master at operating the excavator we rented for two days, but he was actually chomping at the bit to get to do it! This was already the fourth time Bela had scooched my husband out of the driver’s seat of a digger. We had rented a smaller one in previous summers to take out over a hundred cedar shrubs from the hedge that surrounded our property and put up a fence in their place. I had been impressed with my husband’s efforts, who had never operated such a machine in his life and yet had managed to remove a few of the meter thick, two meters high, seventy year old shrubs within as many hours. But once Bela took over, the hedge that had plagued us since we moved to Augsburg in 2000 went down like dominos.

This year the smaller machine was not available, so we rented the next size up to do the heavy lifting of our somewhat ambitious landscaping project. Our son, one of our daughters, and her boyfriend were home for the week to help us extend the patio, dig a foundation for a garden house, remove said concrete wall, and take out a tree stump.

The Stump

The low concrete wall was broken up before I had finished my breakfast, which the kids (in their late twenties now) wheelbarrowed to the trailer hitched to the back of our car, and my husband then drove to the dump. The next order of business was the stump, which Bela, perched high on his excavator throne, was confident would come out without much ado. With the digger now attached, he began mauling the ground around the stump, then, scooping up the grassy dirt, he piled it up in an area of the garden that would have to wait its turn. The digging went fairly quickly, and with every scoop, more of the stump was exposed. Though the mountain of earth, which I now refer to as Mt. Doom and can still be seen from my living room window, kept growing and growing, there seemed to be no bottom to this stump. Not only did it reach deep into the ground, but it sprawled for at least two or more meters in every direction from its center like a giant octopus. My son had gotten a spade and was trying to dig under the long, thick fingers, which were clenching the floor of the only home they’d ever known, so that the digger could get under them and pry them loose. Once under the roots, Bela began an upward leveraging, but instead of the stump or its long tentacles being pried out of its lair, the whole excavator heaved and lifted off the ground. For the next couple of hours, as he tried to wrangle this surly stump from its grip on our garden, our neighbor looked like he was riding a mechanical bull. All he needed was a cowboy hat, and Bronco Bela could have been mistaken for a rodeo attraction.

That is when I started to cry.

The Tree

Looking at the diameter of this stump for a reason why its removal was proving so challenging, Bela concluded that the tree must have been at least forty years old.

He was wrong.

The large cherry tree that I had hired a man to remove in late February was not even half that age. We only began renting the apartment on the second floor of this house 24 years ago, when we returned to Germany from Papua New Guinea in 2000. In, or shortly after 2002, in conjunction with the work our landlady was doing on the north side of the house, we planted an apple tree and a sour-cherry tree. We had no idea what we were doing, and not only were the trees planted in the wrong spot too close to the house and in less than optimal soil, they were also too close together. Subsequently, the apple tree suffered in the shade of the cherry tree and died a few years later. It took a long time for that cherry tree to finally produce any cherries, but, though the fruit bearing years have sometimes been sparse and unpredictable, we have gotten at least some jam and pies out of this tree.

We also got another cherry tree out of it. By 2015 we had bought the house and were finally able to clear away and remove the overgrown flowerbeds left by our landlady. As my husband was clearing the flowerbed planted along that low wall Bela removed for us three weeks ago, the offshoot was only a scrawny two meters high sapling. At the time, I was the one who chose to leave it in, a decision I’v regretted miserably for the last nine years. Unfortunately, by the time I was ready to give this usurper tree its walking papers several years ago, my husband had grown a tree conscience and insisted we keep it. To some degree, it was understandable that he would want it to stay. The cherry blossoms in spring were very pretty… (for five minutes, then they littered our patio for weeks with a continual rain of rotting petals). It did provide shade…(just not anywhere someone would want to sit and enjoy the garden). And of course I think trees are an important feature in, and add character to, any landscaping project… (just not when they randomly and unintentionally crop up in all the wrong places).

Within no time at all, that little sapling grew to three times the size of our original cherry tree. In less than ten years, it was taller even than our three story house. Not only did this tree grow smack in the middle of where I wanted to extend the patio, but it littered our current patio throughout the whole spring, summer, and fall with every phase of its foliage. Not only did this tree tower over and in dangerous proximity to our house, it cast the whole north side in even more shade and turned it green with mildew. Not only did this offshoot not produce any edible fruit of its own, but its crown was so high and so wide, that it hogged all the sunlight from our actual fruit bearing tree, which eventually stopped producing any cherries at all and showed all the signs of a diminishing and dying tree.

So, while my husband and I were at a standstill, the tree seemed to just double in size every year until we were finally able to resolve our differences. And by “resolve our differences,” I mean I just went ahead and hired a guy end of February who took it down in a day’s work, leaving only this stump in the way of our landscaping plans.

The Email

Whatever my body may be doing in any given moment, my mind is always in some kind of discourse with itself. Either it is engaged in a socratic debate about some new/old truth claim taking the world by storm, it is holding court over something someone did or said that annoys me, upset me, or just pissed me off, or it is trying to resolve an internal dilemma between what I really want and what others want from me. It was no different during the days we were all at work in the Garden. In this case, what was front of mind, when I wasn’t actually answering logistical questions and doling out tasks, was an email I had gotten a week before. Though it may have seemed benign on the surface, this email had woken up all of these discourse monkeys, who in turn woke up the rest of the zoo animals that I thought I had fed and put to bed.

There is no doubt in my mind that the author of the email believed they were doing a good thing by writing to me. It was surely with the best of intentions that they offered me their morally laden suggestion of what would be appropriate for me to do in the situation. They had generously taken the time to offer advice in a conflict in which they had the most minimal historical knowledge or insight, no relevant professional competence, and a demonstrable lack of impartiality. But none of this is what had set the monkeys off. Rather, it was the assumption underpinning the admonition that was so noisily disturbing my hard won internal peace about the matter. Boiled down to its most basic message, the email was little more than a notification from a third party debt collector. With the subtlety of a town cryer, the solicitation meant to remind me that in the relationship under question, my accounts would always be in the red. Because of their initial, rudimentary investment, I was now on the ropes indefinitely. I should make regular “interest” deposits to their personal “account,” and they could withdraw any amount at any time from mine without even a hint of recompense, accounting, or restitution. No matter how often, nor how hurtfully, they plundered our relational account and left it in the negative, I would still owe them on that initial capital. In any other context, this would be seen as usury.

In my extended foster family, however, this is simply the debt of gratitude I owe for being taken in as a foster child. Though never said out loud in as many words, the official family myth had always been clear to me: when I had been a child in precarious circumstances, the well meaning, selfless foster parents had done me a favor by taking me under their roof, and, now and forever more, anything other than a “thank you” was out of place… no matter how bad things got. No amount of trauma, danger, neglect, attachment confusion, rejection, resentment, contempt, or diminishment my foster parents might have subjected me to could minimize the enormity of this debt. Or perhaps the extended family just cannot imagine that any of these things had ever taken place. Either way, no matter how much time went by, no matter how much effort went into pretending, mending, and bending my reality to make things add up, that initial capital hung over me like an albatross.

Such a framing of the foster relationship is founded on the deeply disturbing notion that the foster (or adoptive) parents are only the helpers and benefactors, and the children are only ever beneficiaries. This is a profoundly diminishing and dehumanizing message to give to anyone in any relationship. No one wants to exist in a relationship where they are only ever perceived as the one being “helped” and the one solely indebted to the other. Anyone who finds themselves pressed into that role can know for certain that they are actually being used to validate someone else’s idea of themselves as a good person.

But to cast a child in that role with caretakers they did not choose for the life they did not initiate undermines the very foundation of their self-worth and existence. If a child is never told, shown, or given even subtle cues to let her know that her existence, in and of itself, enriches and contributes value to the lives of her caretakers and community, she assumes that she must produce (ie manufacture) that value in order to remove the negative balance in the relationship. Since that is an impossible task, the child either gets stuck in an appeasement treadmill, all efforts oriented toward keeping the peace with those upon whom her very life depends, (ie filling the hole by meeting their needs and expectations rather than her own transformative growth), or, as I had done, gives up entirely and acts out in self-destructive ways. In both cases, the child will struggle to cultivate a healthy sense of self-worth and emotional regulation; find it difficult to discover inherent interests, develop competences, and focus on personal objectives and values; and will often default to a rigid conflict strategy and substitutions for genuine intimacy. From the outset, children in such circumstances will be preoccupied with getting out of the hole they inherited, rather than building a stable identity on the solid ground of being wanted, cherished, and seen as the precious gift they are.

It would be hard to overstate just how crippling such a dowry is. After describing his personal odyssey growing up in the foster system in his memoir, Troubled, Rob Henderson documents what this looks like statistically on a national scale. In Henderson’s comparisons, he isolates the relational instability from economic factors by contrasting the statistical averages for foster children not against averages for the general population but just against children living in poverty and against their own siblings who remained in their family of origin. Henderson writes, “a poor kid in the US is nearly four times more likely to graduate from college than a foster kid, and that only 3% of children from foster homes ever earn a bachelors.” He goes on to say that, “Compared with their siblings who were never placed in foster homes or other types of out-of-home care, kids who are placed in care are four times more likely to abuse drugs, four times more likely to be arrested for a violent crime, three times more likely to be diagnosed with depression or anxiety, and twice as likely to be poor as adults… The findings from the 2021 study show that on average, kids who are placed into care do worse than their siblings who are not.” (Henderson pg. 297). And of course the discrepancy to the general population is even greater.

Those of us who have grown up in this predicament are not just beginning the race far behind the starting line, but we were further handicapped by being tethered to this myth of liability. Living under the shadow of this paradigm means that, even as adults, we divert too much of our emotional energy and resources away from the task of creating a worthy life for ourselves and our progeny and toward feeding the dysfunctional dynamic which continues to demand our allegiance. It was this dogma that seeded itself in my garden early on, took root, sprouted, and shot up to a towering menace in just the ten short years I was with this particular family. But for years afterward, it littered my self-esteem with a sense of inferiority, internal conflict, and a doubting of my instincts. It grew to overshadow the fruitful vegetation of my self-assertion, creative agency, and sense of purpose. And it redirected my energies and resources toward relationships that never bore the fruit of intimacy and mutuality.

But I had felled that tree some years ago.

The monkeys had scattered.

My garden project was well underway.

Yet this email had come in with the weight of a cease and desist order alerting me that I needed to redirect my funds back toward those barren roots.

And as one might trip over a tree stump, I stumbled over it and fell headlong into my internal dialogue.

The Tears

That internal dialogue sounded something like this:

“WHY IS THIS TAKING SO LONG! ARE YOU KIDDING ME?!

I should be over this by now! At my age, other people have a fully finished back yard, and I am still just digging up these barren roots! I’m almost 60, and I am still tripping over these stumps from my past? Just get on with it already! What is taking you so long?! How much digging around it do I gotta do? How much higher does Mount Doom have to get, before I get enough leverage to pry this gnarly thing out of my life for good? I should have nipped this relationship in the bud, spoken up for myself, set better boundaries years earlier than I did! You’re so slow at EVERYTHING! It will be stuck like this FOREVER! Grow up already! Do better! Be better!

SHAME ON ME FOR STRUGGLING WITH THIS FOR SO LONG!”

Not the kind of cheerleaders you want to have in your head on game day. Whenever a gap opens up between what others want me to do and what I want to do, between who I or others want me to be and who I actually am at this moment, it is this troop of negative, self-defeating, mocking mind-monkeys that wants to race in and fill the space. Brené Brown calls these the Shame Gremlins. I have dedicated a lot of time, effort, and resources to taming these shame monkeys, and to a large extent it has paid off. But the debt-solicitation email from my relative had tripped the alarm and set all these old, familiar monkeys into motion again.

That was the zoo inside my head as I walked over to check the progress at the stump-removal-rodeo. There was Bronco Bela riding his mechanical-excavator-bull, tugging and heaving and huffing and hurtling and mauling and digging and scooping and lassoin’ and having a devil of a time trying to get this ten year old stump out of my garden, so that I could move forward with these beautiful landscaping plans of mine. While I was watching the show, suddenly I was aware of another voice whispering something inside that gap between who I wanted to be and who I was.

Without using any words but only the scene before me, it said, “look at him struggle with this stump! Even with all his expertise and experience, even with this heavy-duty machine, even with all this team work taking shovels and axes and even a chain-saw to the long roots, it takes a lot of effort and time and persistence to get these barren roots out of the ground. Be patient. Have hope. Don’t give up.”

And just like that the monkeys were back in their cages, my eyes welled up with tears, and an hour later, Bronco Bela had triumphed over that formidable stump.